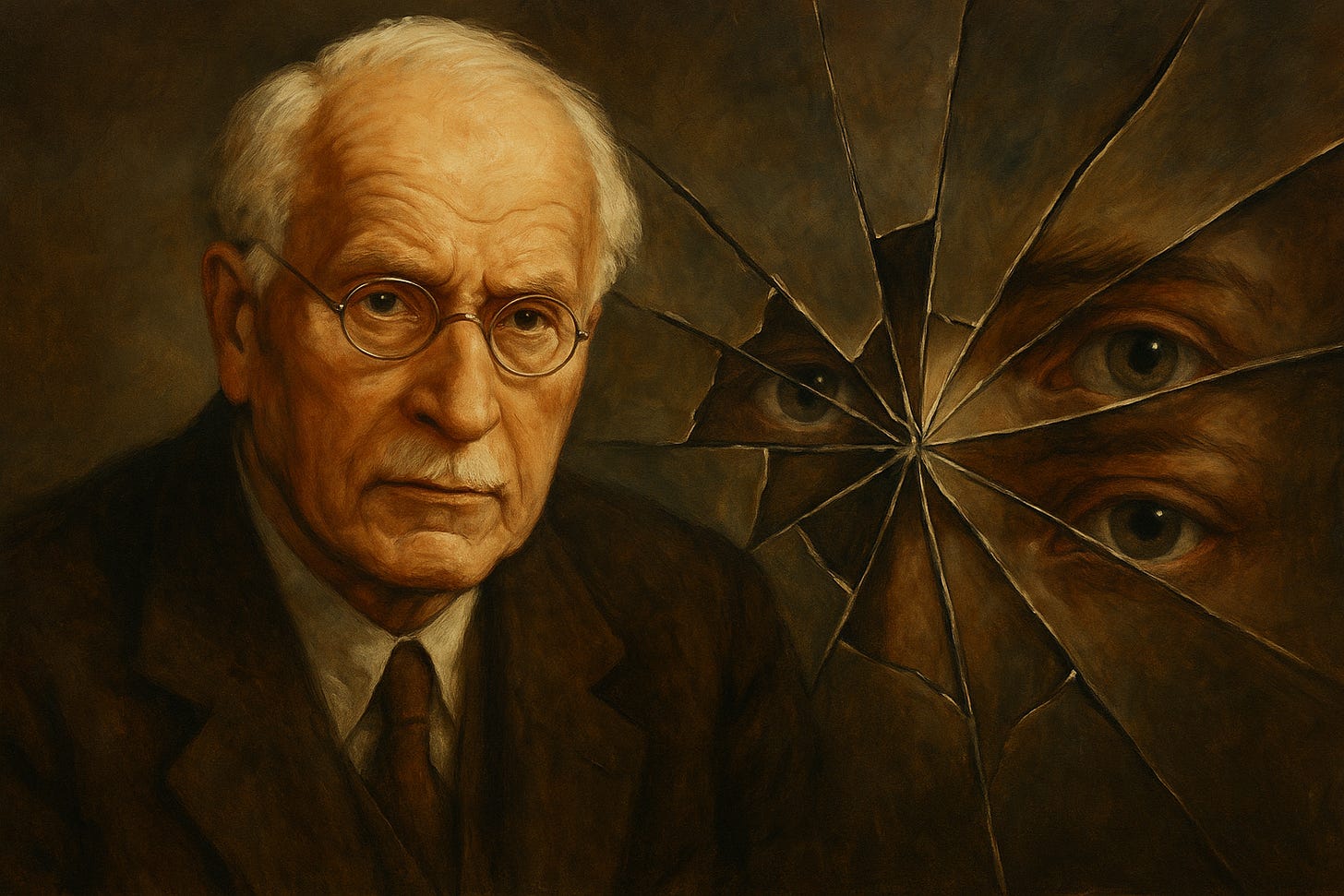

Jung’s Most Dangerous Discovery

The hidden cost of giftedness: when differentiated perception isolates, or transforms.

Carl Jung’s most dangerous discovery wasn’t about mental illness. It was about people who see everything others miss—and why this ability can either destroy them or transform them.

In his clinical practice, Jung encountered individuals with what he described as differentiated perception. They could read micro-expressions, detect hidden emotions, and perceive unconscious patterns that others couldn’t. They saw through social masks, felt the tension in every room, and recognized lies the instant they were told.

To most, that sounds like a gift. But Jung called it dangerous. Not because these people were unstable, but because seeing so much carried a psychological cost society could not bear. Their clarity turned them into mirrors that others refused to look into.

When the unconscious becomes too visible

In 1913, during his own crisis after the break with Freud, Jung worked with a patient who embodied this phenomenon.

She could walk into a room and immediately sense who was in pain, who was resentful, who was hiding rage.

Jung wrote:

“The patient displays an extraordinary capacity for perceiving unconscious contents in others, but this faculty appears to cause her considerable distress rather than advantage.”

She couldn’t engage in small talk. She couldn’t keep a job. She couldn’t sustain friendships. Not because she was disordered—but because her perception stripped away the social fabric that held others together.

Jung realized he wasn’t treating pathology. He was observing what happens when unconscious reality becomes too conscious.

The dangers of seeing everything

Jung identified three core dangers of differentiated perception:

Disrupting collective illusions

Societies depend on unconscious agreements—what we don’t say, what we ignore, the lies we collectively maintain. The person who sees through them destabilizes the whole.

Psychological isolation

To see what others cannot creates a different reality altogether. It doesn’t just cause loneliness; it creates existential exile.

Loss of identity

Absorbing too much of others’ unconscious material leads to participation mystique: dissolving into the collective, losing all sense of self.

Projection and scapegoating

The danger was not only in the perception itself, but in the reaction it triggered. Jung documented how these individuals became magnets for projection. Others unconsciously attacked them for reflecting what they refused to face in themselves.

The one who saw clearly became the scapegoat—blamed for creating problems they merely revealed.

From curse to transformation

Jung believed there were only two outcomes for such individuals: destruction through isolation and overwhelm, or transformation through integration.

This is why he developed the process of individuation:

Recognition — learning to separate what belongs to you from what you absorb from others.

Shadow integration — acknowledging in yourself the very qualities you observe in others, so perception is no longer a weapon.

Conscious participation — engaging with collective dynamics without being consumed by them.

The goal is not to see less, but to see more wisely. Not to feel less deeply, but to relate differently to what you feel.

Consciousness pioneers

Jung saw these people as forerunners—consciousness pioneers. Their suffering was not meaningless. It mirrored what the culture as a whole was not yet ready to face.

“What is not brought to consciousness comes to us as fate.”

Their role was not to suppress their perception, but to learn to carry it in ways that made it usable, survivable, and transformative.

The parallel with giftedness

This is precisely where Jung’s discovery touches on what we now call giftedness.

Highly gifted individuals often report the same experiences Jung described:

They notice the details others miss.

They sense the tension behind the façade.

They see patterns in people, systems, and organizations long before others do.

Like Jung’s patients, they are frequently misunderstood—not because they are wrong, but because they are too accurate. Their perception disrupts collective illusions, and they become scapegoats for the discomfort they expose.

This is why so many gifted individuals feel “too much.” They aren’t too much. They are simply carrying perception that runs ahead of collective readiness.

Jung’s individuation process mirrors the developmental challenge of giftedness:

To recognize what belongs to them and what is absorbed from others.

To integrate their own shadow so that perception doesn’t harden into judgment.

To learn how to stay connected to society without drowning in its unconsciousness.

Giftedness is not simply higher intelligence. It is, at its core, differentiated perception. And like Jung saw, that ability either isolates and destroys—or, if integrated, becomes cultural medicine.

Are you one of them?

If you’ve always been the person who notices what others miss—the mood behind the smile, the lie inside the promise, the pain behind the mask—you are not broken. You are not “too much.”

You are ahead of your time.

The challenge is not to blunt your sight, but to integrate it so that it serves rather than destroys you. That was Jung’s most dangerous discovery: that some people are born with consciousness exceeding collective readiness, and their survival depends on integration.

Your gift is not your burden.

Your unconscious relationship to your gift is.

The question is not whether you should suppress your perception to fit in.

The question is whether you’ll develop the skills to wield it consciously—so it becomes not a curse, but a contribution.

💬 Do you recognize yourself in this?

Share in the comments how you experience your own perception.

📩 Subscribe if you want more of Jung’s insights—together with reflections on giftedness, intensity, and clarity—for people who see what others miss.

I was sent here to read this by my psychologist. I sought him out for some advice, about whether or not I was being unreasonable in my romantic relationship. I've been a human polygraph for the last 25+ years. I first remember having to pretend I didn't know what was going on in order to avoid conflict, when I was 10. Somewhere in my mid-twenties, I realized I had a gift that I couldn't explain, and started trying to figure out what the mechanism was that made me different. I had an abnormally good heart, in terms of blood pressure, resting heart rate, and cardio ability, so I thought maybe it was an interaction of the magnetic fields produced by our hearts. The heart, acting as a transceiver, with mine being physically more powerful. Regardless of whether my theory was correct, it didn't take me long to come to the conclusion that always knowing when you're being lied to, is very painful. I know everyone in my life better than they want to know themselves, and some of them hate me for it. My father suffered daily agony in his back and leg for 20 years, until I told him he had a pain syndrome and essentially hypnotized him out of it. He's been pain free for almost a decade, though we no longer speak. They feel exposed. And I don't know how Jung picked up on the fact that people would project themselves onto me, but that's ever present, and often to an outrageous degree. I am incredibly isolated, though reading all of this has given me hope that I may be able to find contentment. Despite all of this, if I could snap my fingers and have it go away, I'd say no and keep my curse.

Seeing more wisely is a useful suggestion.